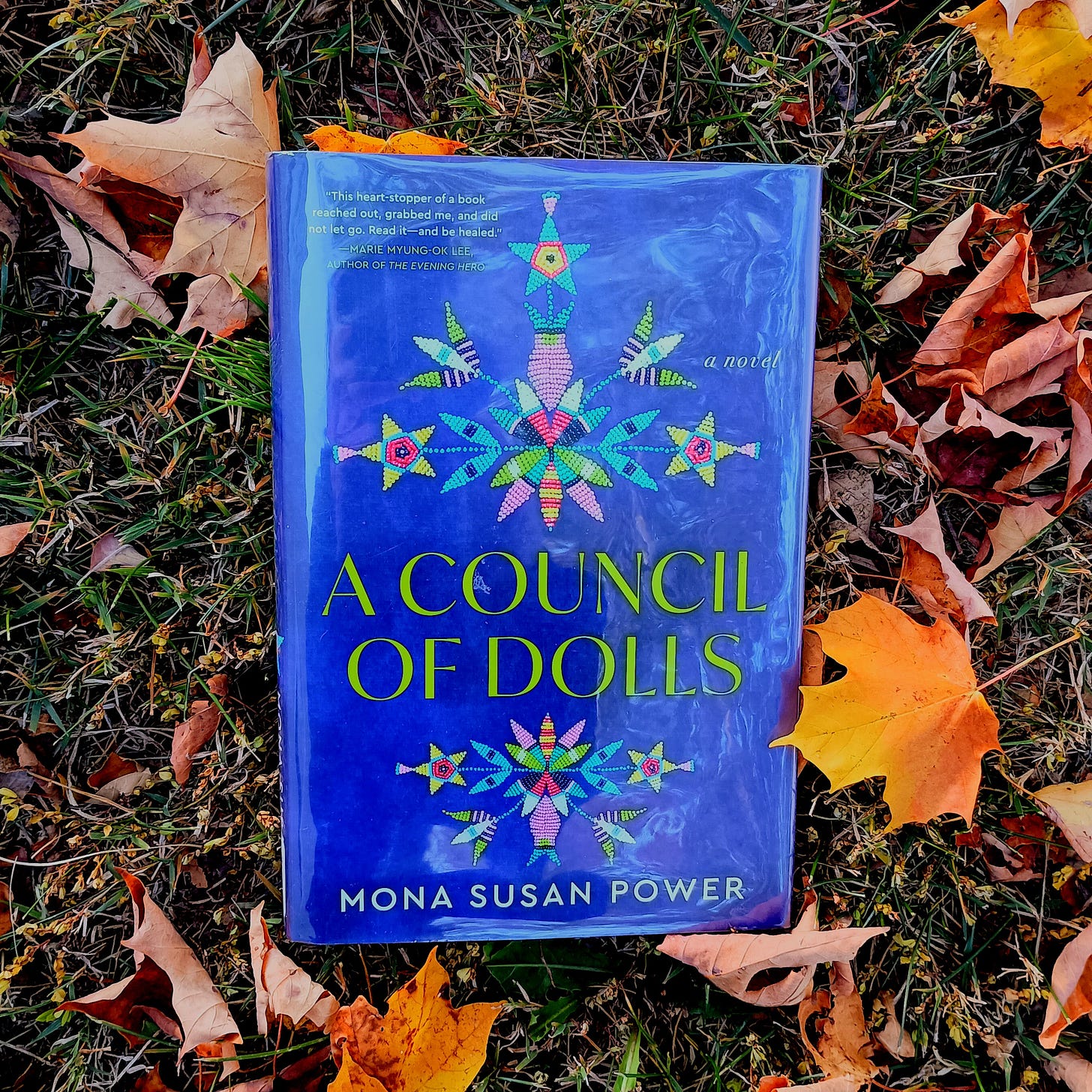

Title: A Council of Dolls

Author: Mona Susan Power

Publisher: Mariner Books

Publication Year: 2023

ISBN: 9780063281097

Rating: 4 stars

Last December, I read The Grass Dancer by Mona Susan Power (published under the name Susan Power back in the mid-90s). It was well written, but I just had a hard time getting into it and getting through it. Her short story “Dead Owls” was featured in Never Whistle at Night and I liked that story a lot better, so I decided to give A Council of Dolls, one of her newer books, a try. Once again, the book was very well-written, but the topics covered are so sad that it took me a long time to read, but I liked the ending and was glad that I gave Power another try.

This book is split between the perspective of three Dakota girls: “Sissy” who lives in Chicago in the 1960s, Lillian or Lily who lives in South Dakota and Missouri in the 1930s, and Cora who lives in South Dakota and Pennsylvania in the 1900s. The story then ends back on “Sissy,” who has legally changed her name to Jesse and doesn’t use that nickname anymore, in Minnesota in the 2010s. In addition to moving backward in history before moving forward, the book also moves back up a family tree. Jesse is Lillian’s daughter and Lillian is Cora’s daughter. Cora’s father was an interpreter for Standing Bull, so the family has been a vital part of tribal life as the government destroys their way of life. Both Lillian and Cora are forced away from their families as small children to attend boarding schools where students are severely beaten and punished for speaking their native language and where white teachers and staff separate them from their people and their heritage.

The other thing all three girls have in common is that they each have a doll that plays a big part in their lives. For Cora, it is a doll made of buckskin back before the Whitestone Hill Massacre in 1863 named Winona. Winona was made to console a mother who had lost her baby. She was then passed down. While the girl who owned her died in the massacre, Winona was rescued by a dog running after the survivors. She continues to be passed down until she ends up with Cora (who was born during the blizzard featured in The Children’s Blizzard). When Cora is twelve, she is sent to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania (in the book, her parents are given the choice to send her even though it isn’t much of a choice, which isn’t the case for many other children at Carlisle, so I was a little confused about that). She will not be allowed to return home until she graduates school at eighteen. She takes Winona with her, but upon arriving at the school, everything the children have with them is burned, including Winona. Cora is devastated and burns her arms trying to save Winona from the fire. After the fire is out, Jack, a boy Cora befriended on the train who is half Dakota and half white, digs through the ashes and brings Cora a stone that had been in Winona and was her heart. Through having the stone, Cora is still able to feel Winona’s presence in her life. Cora excels at school, but Jack, while intelligent, struggles. He is constantly fighting against the control of the white school and to preserve his own culture and beliefs and is severely punished.

Lillian, the daughter of Cora and Jack, has never had a toy. In a home with too many kids and too little resources, toys have never been a priority. In his adulthood, Jack has been broken by the system. Constantly denied civil treatment and opportunities to succeed, Jack is drunk most of the time and can be verbally abusive to Cora and their children. Cora has a way of becoming invisible when Jack is home to avoid setting him off and the children constantly feel like they are walking on eggshells around him. Outside of the home, Cora is an important part of the community and is often called upon to help those in need. Lillian is academically gifted like her mother. Lillian and her slightly older sister Blanche attend a boarding school in Missouri while their older sister and all of their brothers are sent to a different school. Likely because of the financial hardships of the Great Depression, the children are now allowed to leave their schools to go home for the summer and holidays unlike their parents. Blanche inherited more of her father’s fiery spirit, so while also intelligent, is more likely to get in trouble at school. After performing a reading at a Christmas Pageant, a charity gives Lillian a Shirley Temple doll she names Mae. She has always wanted a doll and loves Mae so much. However, when it becomes clear that a friend of Lillian’s is about to die of tuberculosis and that little girl has always wanted a doll, Cora suggests that maybe Lillian should give Mae to her. Lillian doesn’t want to, but doesn’t know how to live with herself if she doesn’t, so she gives Mae away. A few days later, the girl dies and Mae is buried with her, which breaks Lillian’s heart. When Lillian returns back to school, she has a hard road ahead of her. Somehow Mae’s spirit is able to fight her way out of the grave to be with Lillian while she faces some of the biggest hardships of her life.

“Sissy” (aka Jesse) is the daughter of Lillian and Cornelius Holy Thunder, a boy Lillian met at the boarding school. Sissy’s legal name is Lillian but she doesn’t want to go by her mother’s name so she is called by a slew of nicknames. Lillian can be an emotionally difficult mother. With her past traumas, she can be prickly and doesn’t like to be touched. On her up days, she can be the most wonderful person to be around, but on her down days she can be violent and hurtful and sometimes can’t get out of bed. Cornelius and Sissy are close, but with his time consuming job as a newspaper reporter, he is not often home, leaving Sissy to weather her mother’s moods on her own. Or almost on her own. One Christmas, Cornelius buys Sissy a Thumbelina doll she calls Ethel after her godmother. Ethel has beautiful dark hair and darker skin that is the same color as Sissy’s. Ethel helps Sissy brave the ups and downs of her mother’s personality and provides comfort when Sissy must battle her own tragedy. Growing up in 1960s Chicago, Sissy is thankfully safe from the harmful boarding school experience her parents and grandparents faced1, but instead she lives in a world where she is still ostracized as “other” and watches as she and those around her struggle to reclaim their culture and their history and battle the lasting legacy colonialism has left on their people.

We meet up with Sissy, now Jesse, again at the end of the book. She is still struggling to make peace with her past and reclaim her identity. She still has a lot of unresolved trauma from growing up in her home and the generational trauma of having her land and culture stolen from her. She is a college professor and writer living in Minnesota and she collects first editions by Indigenous writers. While searching eBay for these books one day, she stumbles across a book that has a white Thumbelina doll just like Ethel on the cover. The reminder prompts her to open a box of things from her childhood home that has been forgotten in a closet since she moved out. She finds Ethel the doll, but in addition to Ethel the doll, she also finds a Shirley Temple doll (the same one Mae had been) that the human Ethel bought for Lillian on one of her bad days, and the new Winona that Cora’s mother had made her as a graduation gift, but that contains the old Winona’s heart. As she finds the dolls, Jesse hears them talking to her the way Ethel the doll used to talk to her as a child. They all tell her their stories as well as the stories of the girls they tried to save. Through hearing and transcribing these stories, Jesse is able to more fully understand the lives of the women who came before her and how what happened to them has trickled down to her. This understanding allows her to start to make some peace with her past and allow herself to forgive herself and move forward. It allows her to move beyond just trying to survive and into trying to live.

This story was really powerful to me. While I cannot even begin to comprehend the experience of being Native American in the US, I did relate to the parts of the story about how not understanding the trauma of your foremothers can impact them and you. I think any daughter can relate to that even if they have been very privileged. It makes me think about the importance of trying to make amends for your own shortcomings and issues while also trying to remember to have grace and be forgiving of the ways history we don’t fully understand can impact the ways others interact with us. While many of the struggles in this book are specific to Native Americans, there are many parts of this story that can be interpreted universally.

As a white person, I was also really moved by the stories of these children in the boarding schools. I never learned about Native American boarding schools in my history classes. I remember reading a couple of books about Native American kids in mission schools as a child (I don’t remember the titles and a quick Google search didn’t turn up anything familiar), but those books glossed over a lot of the most horrible aspects because they were written for children. I think this is a crucial part of US History that needs to be taught and that white people need to educate themselves on. It is also especially topical because President Biden just issued an apology for these atrocities and the deaths of over 900 children in these schools on October 25th, 2024. As he said in his remarks, this apology is long overdue and in my own opinion, it is far too little far too late.

I think this book is important, because while fictional, it can be a powerful tool to educate yourself on the things we aren’t taught in history class and it has enough universal appeal to make it relatable for most readers. I also loved the way it explores the challenges in mother-daughter relationships and how even when you try to protect your children, you are not always able to do so completely. It was definitely an emotional read, and that can make it hard to want to pick it up, but I think it is going to stay with me for a long time.

It is important to note that several of these boarding schools were open until the late 1960s, but Sissy doesn’t attend one