Three Poetry Collections by Native American Writers

While I was researching which books I’d like to highlight for Native American Heritage Month, I came across an Instagram post by Indigenous Bookshelf with a list of poetry collections written by Native Americans. You know that I love poetry, so I decided to check out three of these collections to highlight this month.

So you may ask, why these three? Well there are two reasons: 1. these collections all sounded interesting and appealing to me 2. these are the collections I could get my hands on. Many of the books featured in the Instagram post are not books in my local library’s collection and they are hard to find for a reasonable price online. I was disheartened to discover that it is difficult for readers to get their hands on these books, but I think that just goes to show some of the issues of access to Indigenous culture and writing that are unfortunately part of our North American culture.

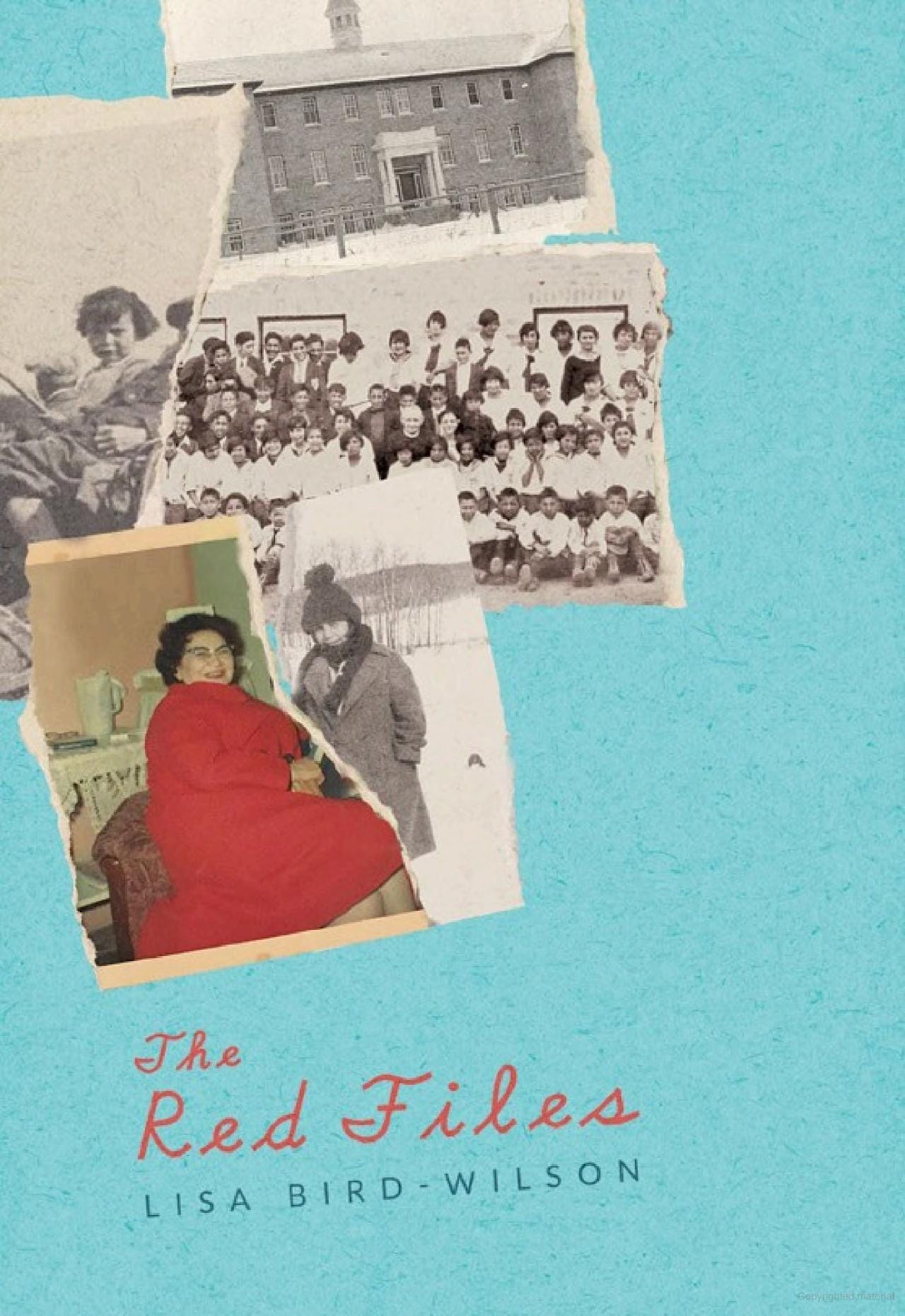

The Red Files by Lisa Bird-Wilson

Title: The Red Files

Author: Lisa Bird-Wilson

Publisher: Nightwood Editions

Publication Year: 2016

ISBN: 9789889710672

Rating: 4 stars

Lisa Bird-Wilson is a Canadian poet and a large portion of this book deals with the existence and aftermath of the Canadian residential school system, similar to the one we had in the US. This is her debut collection and explores the way the school system and its aftermath has torn apart Indigenous families. According to Bird-Wilson’s website, the book title comes from the way the Canadian government divided residential school archives into “black files” and “red files.” Much of the inspiration from this book came from photos and documents Bird-Wilson found in her archival research.

That seems most clear to me in the first section of the book where many of the poems seem to be inspired by photographs. Despite many of the photos not providing much information about their subjects, Bird-Wilson describes them and the circumstances in which they were taken so well that it feels as if she was present for all of them.

I was especially moved by “The Apology,” a poem seemingly about Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s 2008 apology on behalf of the Government of Canada to the survivors of residential schools and their families. The poem highlights how a simple apology, especially one that seems especially staged for the media, doesn’t even come close to atoning for the abuse the children suffered at these schools and the ways the legacies of these schools and systemic racism against Native Canadians is still impacting people today. The poem highlights how despite this apology, many Native communities still lack access to clean water or a quality education and how without action to back it up, this apology is meaningless. I thought the poem was very evocative and as I mentioned earlier this month, President Biden only just issued an apology for the Native American boarding schools in the US this year, sixteen years after the Canadian Prime Minister issued an apology. And almost two decades after Harper’s apology, still very little has been done in either country to right the systemic injustices in place.

Indianland by Lesley Belleau

Title: Indianland

Author: Lesley Belleau

Publisher: ARP Books

Publication Year: 2017

ISBN: 9781927886021

Rating: 3.5 stars

Lesley Belleau is another Native Canadian poet. Her poems are written mostly in English with Ojibwe sprinkled in. Sometimes translations are provided (especially if the Ojibwe word appears in the title) and sometimes they are not. In trying to look up some of these words, I discovered that there doesn’t seem to be a very robust set of resources for translating Ojibwe to English. I ended up using The Ojibwe People’s Dictionary from the University of Minnesota, but I still never found a translation for several of the words. I’m not sure if that is due to regional differences in spelling or something else. I knew that due to the work done by the residential schools that many native languages face extinction, but are experiencing a resurgence, but I was surprised by how hard it was to find the resources to translate Ojibwe.

I feel pretty comfortable classifying this collection as a feminist poetry collection. Many of the poems focus on women’s experience both in history and in a timeless space. Many of the poems have pretty graphic descriptions of consensual sex or rape and sexual assault, so be prepared for those. I’m usually pretty chill when it comes to writing about those topics, but I found myself clutching my pearls a couple of times here (especially in the ones about non-consensual encounters) because of how graphic yet also metaphorical they were and I think I would have done better if I was a little more prepared.

Many of the poems are about the female collective—women working together to accomplish tasks and achieve their goals like gathering plants and childbirth. Many of the poems also touch on female family lineage and how love and traditions are passed down from one generation to another. Belleau also writes about the huge number of missing and murdered Indigenous women who are not receiving legal justice or media attention.

In the poem “Niibinabe” (I don’t have a translation for that), she writes “How does a country endure on top of piles and piles and piles and piles/ Of disposed women’s bodies? How can a conscience persist here?” (42). This sentiment is obviously applicable to Indigenous women in Canada, but also echoed to me all the times in history that countries have endured despite the murder of women.

In the poem “Desire,” she makes a Biblical reference that I really enjoyed writing, “the length of your hair a shadow/that made me think of Delilah/and how she knew about power/and how to steal it” (36). As someone who endured a lot of years of Catholic education, I’ve always liked the stories of women like Delilah and Judith who are out there thwarting men and making them cry or decapitating them. I did think the allusion to Delilah was interesting in this poem. As you might guess from the title, this is one of the more sexual poems and is about a consensual sexual encounter between the speaker and her partner. In the afterglow, she is holding his head on her chest and notices his hair. She thinks of Delilah, but instead braids his hair “smoothing the ends with our/juices” (36) (one of the lines where she lost me a little bit). The couple in the poem seems to be happy and loving, yet I don’t think many would describe Samson and Delilah as a #goals type of couple. I also know that many Native American groups have strong feelings about hair and cutting it and how to dispose of the hair once it is cut. This obviously differs from person to person, tribe to tribe, and throughout history, so I’m not sure how mainstream Ojibwe culture past or present views the issue. Going back to the residential schools (which are mentioned a few times in this collection), I know many schools cut off the hair of all of their students to further break their spirits and separate them from their culture. Because hair and cutting hair can be such a loaded topic, I was kind of confused to see that allusion in what is otherwise a very loving poem. I think the focus, however, is on women taking back power, which added an interesting dimension to this poem for me.

My favorite and in my opinion the most heartbreaking poem in this collection is called “Mothersong.” The poem opens with a woman surrounded by other women giving birth to her daughter and wanting to bring her daughter safely into the world even though she feels she will die in the process. After her daughter is born, they both survive and she is awed every day to experience the joy of life through her daughter’s eyes. The speaker says, “…I turn to my husband, wondering at/ the life we’ve been given” (96). However, the next year when her husband is away, two white men enter their home at night and take the daughter away to a residential school, with no warning and against everyone’s will. Her last sight of her daughter is the child screaming and kicking and pleading for help with her eyes as she is taken away in a truck. The speaker enters into a deep depression and almost dies until her husband calls some women to come and nurse her back to health. She eventually recovers, but the damage is done. The poem ends, “and I live here, quietly./ silence, my mothersong sliced/ from my voicewalls, stolen./ quiet.” (100). This poem made me cry.

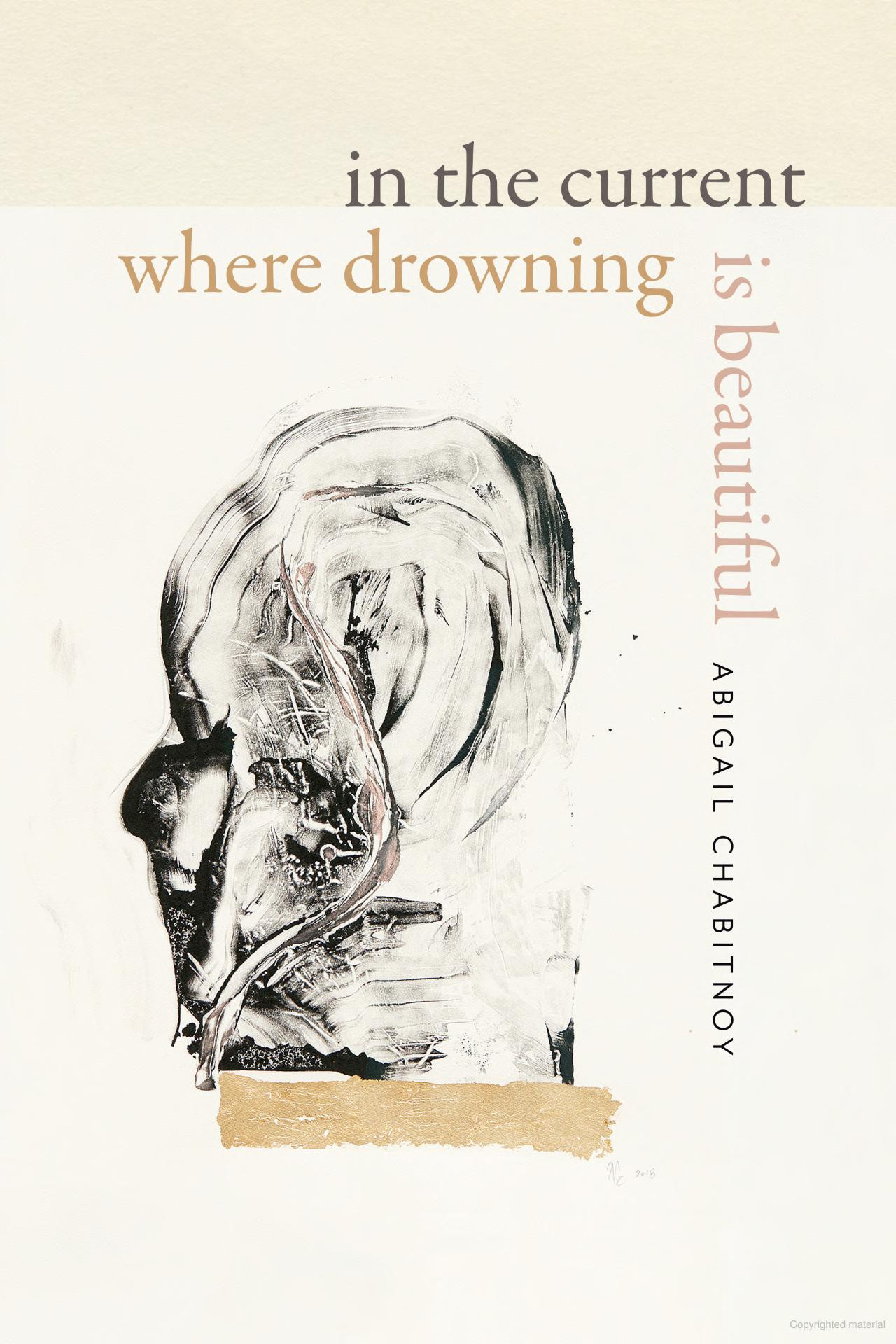

In the Current Where Drowning is Beautiful by Abigail Chabitnoy

Title: In the Current Where Drowning is Beautiful

Author: Abigail Chabitnoy

Publisher: Wesleyan University Press

Publication Year: 2022

ISBN: 9780819500137

Rating: 4 stars

Abigail Chabitnoy is a Koniag descendent and a member of Tangirnaq Native Village in Kodiak, Alaska. These poems are written mostly in English with words and phrases of what I believe is Alutiiq woven in. Most of the Alutiiq is connected to footnotes that seemingly provide a translation but because of the way the footnotes often seem to continue the poem on rather than just translate, I’m not sure how direct of a translation it is. Once again, I was not very successful in translating, so I really can’t confirm how close the footnotes are nor that the language is absolutely Alutiiq to begin with. So once again, I am learning how few accessibility tools there are out there for people interested in Native American languages.

This collection explores the connections between women, environmental changes due to climate change, and social justice. As someone who has a lot of climate change anxiety, trying to read this collection while awaiting the results of the 2024 US election made this a challenging read for me. The language and the poetry is beautiful but the topics are difficult.

The book is divided into sections, each section having to do with part of a wave (wave/swell, wavelength, wave crest, wave height, wave trough). Many of the poems touch on themes of the importance of water and how as sea levels rise, we are both flooded but left without freshwater for drinking and how changes in temperature and environment impact (usually by reducing) the wildlife around us. We had to turn our air conditioner back on last night and are bracing for another 80° day in November, so I know how that feels. Several poems in the book are directed toward a “some day daughter” or a “future daughter” and talk about the legacy we are leaving behind for future generations. Like with Indianland, this is a feminist poetry collection and many of the poems touch on the role of women and how we are treated in the world. One of the poems was called “When You Can’t Throw All the Men into the Ocean and Start Over,” which was a title I particularly liked.

In “Camouflage, Defense, and Predation Being Among the Reasons,” Chabitnoy writes,

"I sometimes feel with my mother we are nestled in the hand of god only god is female and in her hand is a hole we must pass through to be caught to feed the men again and again to feed the women and the children and the men-- And it's not personal, or it is, but the hand is thinking of closing. I think the hand is closing. After all, you can only throw a fish so many times before bad heart, before traumatized, before it looks like a world with a lot of dead women." (31)

Chabitnoy is doing a lot of interesting things with spacing in this collection, but to me this passage echoed the “piles and piles and piles and piles” of dead women from Belleau’s poem. Much like with the environment, this poem talks of how you can only take so much from something or someone before there is nothing left to give.

My favorite poem in this collection is called “How it Goes.” The title of this poem comes from the incident at the March for Life (an anti-abortion march and rally in Washington, D.C.) in January of 2019. If you remember this event, a group of students from Covington Catholic High School in Kentucky wearing MAGA hats were involved in an altercation with Nathan Phillips, a Native American elder and the media had a field day painting one group and then the other as the victim of the exchange. In a video of the confrontation, one of the male students is heard to say, “Land gets stolen. That’s how it works. It’s the way of the world.” Chabitnoy says in the notes section at the end of the book that she does not think it is true that this boy meant no disrespect in his comment, but she does think he had likely never been taught better than to say something like that aloud.

For Chabitnoy, the irony in this event is that even in attending a “pro-life” event, marchers are still making clear that the “right to life” and “protection of children” only extends to a certain subset of children. In this poem, she cites several powerful numbers (all from the time the poem was written in 2019): 250 or 559 or >400 children forcibly separated from their parents at the southern border under the first Trump administration; between 2,000 and 14,000 immigrant children held in U.S. detention centers; 186 children buried at the Carlisle Indian School and >10,000 children separated from their families and forced to attend that school; 500 missing, 2,000 murdered, and 15,000 at risk Indigenous women; between 200 and 2,000 massacred Alutiiq people (mostly women and children) in the Awa’uq Massacre in 1784. As you can tell, these numbers were not closely kept and vary widely depending on source, which is very concerning considering we currently don’t seem know how many children we have in government custody at the moment.

Beyond the sheer force of those numbers, the poem is haunting and beautiful and about the way “land” from the quote can easily be transformed to mean “women” or “children” or other things people consider property. How the “right to life” doesn’t exist equally for every person in this country and how it hasn’t since Columbus arrived in 1492.

While all three of these collections come from different cultures and deal with different topics and themes, I thought it was really inspiring to see some of the commonalities that run through them and how differences are handled. I enjoyed these collections and I’d like to try to find some of the others from the Instagram post.